“The House I Live In”: New Documentary Exposes Economic, Moral Failure of U.S. War on Drugs

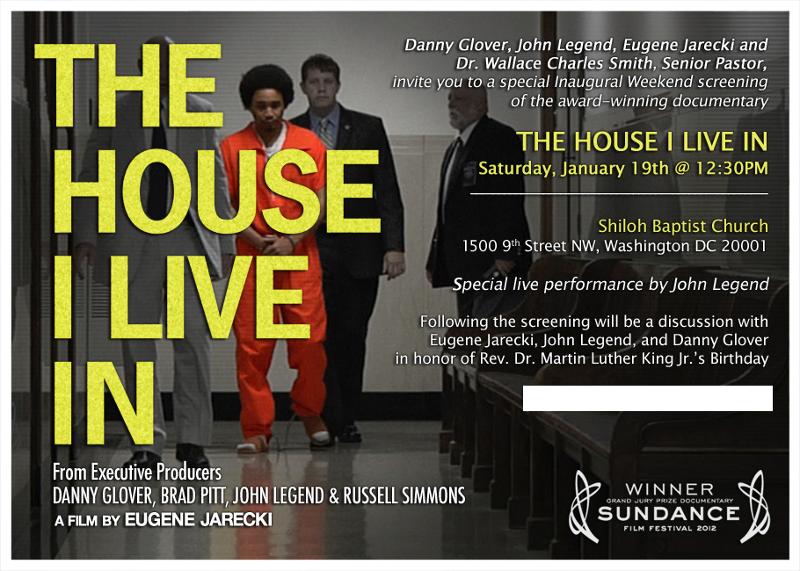

This weekend the top documentary prize at the Sundance Film Festival went to “The House I Live In,” which questions why the United States has spent more than $1 trillion on drug arrests in the past 40 years, and yet drugs are cheaper, purer and more available today than ever. The film examines the economic, as well as the moral and practical, failures of the so-called “war on drugs” and calls on the United States to approach drug abuse not as a “war,” but as a matter of public health. We need “a very changed dialogue in this country that understands drugs as a public health concern and not a criminal justice concern,” says the film’s director, Eugene Jarecki. “That means the system has to say, ‘We were wrong.'” We also speak with Nannie Jeter, who helped raise Jarecki as her own son succumbed to drug addiction and is highlighted in the film. We air clips from the film, featuring Michelle Alexander, author of “The New Jim Crow”; Canadian physician and bestselling author, Gabor Maté; and David Simon, creator of “The Wire.” [includes rush transcript]

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: As the Republican presidential candidates challenge President Obama with competing visions for how to improve the struggling U.S. economy, a new documentary questions the amount of money this country spends on the so-called “war on drugs.” Over the last 40 years, more than 45 million drug-related arrests have cost an estimated $1 trillion. Yet drugs are cheaper, purer and more available today than ever. The documentary is called The House I Live In. It examines the economic, as well as the moral and practical, failures of the war on drugs and calls on the U.S. to approach drug abuse not as a war, but as a matter of public health.

The House I Live In won the Grand Jury Prize for U.S. Documentary this past weekend at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, the largest independent film showcase in the country. Democracy Now! was there earlier in the week, and I spoke with the film’s director, Eugene Jarecki, along with one of his main characters in the film, Nannie Jeter, about what inspired him to look at the war on drugs.

EUGENE JARECKI: The film is a movie which was very much inspired by Nannie Jeter, who’s sitting with me. I grew up—I’ve known Nannie my whole life. Nannie worked with my family from the time I was a toddler and taught me a great deal about life and about the struggles of people in this country. And as I grew up, you know, I was very close with Nannie, and I was very close with members of her family, some of whom have come here to Sundance. And I grew up, and I’ve had a pretty privileged life. I’ve been able to become a filmmaker. I’ve met opportunity along the way. I’ve had a lot of positive experiences. And I noticed that young people in her family, who were growing up alongside me, were not having that kind of experience, and I wanted to know why.

I wanted to know why people I love and care about—I mean, I knew that we were all living in a post-civil-rights America. Nannie Jeter is African American. Her family is African American. But I thought that was all supposed to get better, and so I thought we were on a path all together, as I think a lot of people did. And yet, despite certain gains that African Americans have made, for the masses of black people in this country, it remains a pretty tough road to hoe. And I wanted to know what went wrong. And I began to learn that from Nannie, and that really sent me on a journey, because I started to ask her my first questions about what she thought had happened, even within her own family and community.

AMY GOODMAN: Nannie Jeter, this is a story about the so-called drug war in America?

NANNIE JETER: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about your family in the context of that.

NANNIE JETER: Well, my son, which is deceased, his name is James Jeter, my youngest son. And he got on drugs when he was about 14. As he became more addicted to drugs, I couldn’t control him, and I could not discipline him. And so many things would disappear from the house: clothes and rent money, food money, everything that you left in your house and you trust your kids with. And it was like a, like I said, genie. You would see it today, and at nighttime it wasn’t there. And it was your last. And drug played that part in my life, that I became—I just hate anything to do with drugs, because it destroyed a family. And back in those days, you would be walking or taking the bus, and you would see someone else’s son taking furniture out of their neighbor house or their own parents’ house, selling it for this drug. And even back in those years, it still haven’t changed. There are—of the same thing for drugs.

I have a great-niece that had four children, and she is addicted to drugs. And for a while, she’ll go into rehab. And it still comes back to haunt her. It’s like something that she can’t get rid of. And that was the same thing with my son. And at the end, he just got so tired of drugs, and he had injected himself so much with drugs, it was in his—in his feet. Just, you can’t even imagine the abuse, the suffering that people go through addicted to drugs. And it is a sad thing.

And our—this country, where we can go into other countries and try to straighten that out, and we can’t even straighten out. And it’s a black thing, and it’s more prison to put young blacks in, all the blacks in, and there’s nothing been done about it. If you can send someone to the moon and all of the things that we are doing in this country, you sure can eliminate the drugs that’s coming. That’s my faith and my belief. And even in our own—in New Haven, I remember back last year when a lot of white teenagers were being killed at 16 with their driving license. We had a government that changed the rules so that we wouldn’t lose so many white teenagers. But it never was a rule—you don’t even hear any politician mention drugs or anything, you know, and that’s what really, really bother me an awful lot, that it destroyed people. It’s no trust there.

And different relatives, you can’t leave in your home. You have to lock up stuff. And stuff that you just bought and on credit and trying to pay for and live American—halfway—dream, it’s being stolen. It’s being stolen. And my son were—he would wait for the mailman. I had—my aunt was living. And he would wait ’til she would come to get mail, so he could get in the house and to take whatever that he could sell. And you beg, cry. You love. You love. You hate. It’s nothing that you could do about it. And still, I have a niece that have a family that love her, and her kids now have reject her. She wants to get off drug. I do not believe that people do not want to get off drug. And you hear testimony of womens that is on drugs. It’s something that our country can change. We can change everything else.

AMY GOODMAN: And I think that’s really what this film is about. You have these facts and figures peppered throughout this film, Eugene. African Americans make up roughly 13 percent of the U.S. population, 14 percent of the drug users, yet they represent 56 percent of those incarcerated—

EUGENE JARECKI: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —for drug crimes.

EUGENE JARECKI: Have 90 percent in the federal system. So you have a 13 percent population. I mean, most people, for example, when they think of crack, they think, because that’s what the media has told us, that crack is a black drug. The fact is, blacks don’t use crack more than anybody else. And as a result, because blacks are only 13 percent of the country, they’re 13 percent of the crack users. So the remaining crack users, i.e. the majority, are white and brown. That’s something you would never even imagine, because that’s not how the laws are applied, it’s not how we hear about it.

AMY GOODMAN: Set up this clip for us around crack.

EUGENE JARECKI: Sure. Well, crack—you know, the crack phenomenon, which exploded in the 1980s, was built on a lie. Len Bias, the basketball player, had died of a heart issue related perhaps to cocaine. It was never even fully determined. And it was pretended at the time that it was crack. And Tip O’Neill and other Democrats, particularly, at that time wanted to appear tough on crime, like their Republican counterparts, and so they used Len Bias and other sort of “shock and awe” stories about crack to say there’s this terrible new drug that is so destructive.

And I totally empathize that—with Nannie, about losses she has seen, that people have experienced, due to drugs. That’s no question. But what you’ll see in the clip is the way in which lies and propaganda by the U.S. government about drugs not only make—they make the problem worse, because they don’t solve the problem that the drug may represent, which is a public health problem. Her son was a victim of a public health problem. What do you do about addictive drugs in the world? That’s a question that’s worth debating and worth figuring out the public health policies for. But instead what we’ll see is, the way that Ronald Reagan and others of both parties have used these issues is to make it a criminal justice opportunity, a law opportunity.

CHILD: Don’t take my mother, please!

MICHELLE ALEXANDER: When Reagan announced that he was planning to rev up the drug war, more than ever, it was political opportunity, because at the time drug crime was actually on the decline, not on the rise. Less than 2 percent of the American population even identifies drugs as the nation’s top priority. But then, of course, they got lucky.

BOB SCHIEFFER: Crack cocaine.

DAN RATHER: Crack, the super-addictive and deadly cocaine concentrate.

MICHELLE ALEXANDER: Crack hit the streets, and suddenly there was a hysteria about this brand new demon-like form of cocaine.

PRESIDENT RONALD REAGAN: Today, there’s a new epidemic: smokable cocaine, otherwise known as crack. It is an uncontrolled fire.

The American people want their government to get tough and to go on the offensive. That’s exactly what we intend, with more ferocity than ever before.

POLICE OFFICER 1: Police, freeze!

POLICE OFFICER 2: Here is your crack.

MARK MAUER: It’s inescapable that the image of the crack user at the time was a young black man, whether or not that was correct.

CARL HART: What we saw were images of black urbanites on TV smoking crack cocaine over and over and over. And then these incredible stories were being associated with crack cocaine, and they were taken as fact.

HAROLD DOW: The drug so powerful it will empty the money from your pockets, make you sell the watch off your wrist, the clothes off your back.

ROBERT STUTMAN: Or kill your mother. Yep, that’s what we’re seeing.

CARL HART: But if you go back to the 1920s and the ’30s, this is what people were saying about marijuana.

FILM CLIP: Alvin takes that frying pan from the stove and kills his mother with it. Not a very nice thing to look at, but this is marijuana.

CARL HART: If you say that now in our society, people will look at you like you’re crazy.

AMY GOODMAN: An excerpt of the film, The House I Live In. It won the Grand Jury Prize for U.S. Documentary this weekend at the Sundance Film Festival. We’ll be back with the director, Eugene Jarecki, and Nannie Jeter, one of the subjects of his film, in a moment.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return to my conversation about the so-called “war on drugs” with director Eugene Jarecki. His film, The House I Live In, won the Grand Jury Prize for U.S. Documentary this past weekend at Sundance Film Festival. I spoke with Eugene, along with the woman who helped to raise him, one of the film’s main characters, Nannie Jeter. I asked him about the costs of the drug war.

EUGENE JARECKI: You know, we’ve spent, in the years of the drug war—the drug war, as we know it today, started in 1971, when Richard Nixon called it a “drug war.” We had had drug laws in this country going back to the 1800s, which we go into in the film a little bit. But it was Nixon who made it a war. And when you make something a war, what comes with that are all the problems that wars bring: profiteering, corruption, fear mongering, victims, aggressors, an industrial sector that emerges.

Just like the weapons business, what we discovered is there is a giant and sort of secret network of people in this country. It’s not even that secret. It’s just secret if you don’t realize it’s there. But there’s this vast spectrum of people. You know, when you put a prison in a town, that prison needs food facilities, so somebody’s got to make the food. And this isn’t just about jobs. It’s about companies that then service these institutions. You need laundry service. You need phone service. We went to a trade show, for example, where we saw, as if we were looking at people who were selling like plumbing hardware, people selling all the stuff you need to make a bigger, better, stronger, tougher prison.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to that trade show for just one minute.

RESTRAIN CHAIR SPOKESPERSON: This chair, in comparison to other types of restrain chairs, is the most humane, and it’s not restrictive.

BERNARD KERIK: The war on drugs has to be a war at every level. It has to be a war on the streets of the cities. It has to be a war at the state level, and it has to be a war at the federal level. It’s just like fighting the war on terrorism.

QURAN SALESPERSON: Before, in the prisons, I guess the only choice was, you could get a Torah or a Bible. Things have changed now.

Anybody want their free copy of the Quran?

RICHARD LAWRENCE MILLER: All sorts of people start to get a vested interest, a financial interest, in keeping the system going.

RESTRAIN CHAIR SPOKESPERSON: We’re in the business of supplying Corrections with products. It’s a growing market, prisons. There is a lot of prisoners in the United States.

CCA SPOKESPERSON: This company, CCA, we are the leader and the largest in the world, as far as private prisons and jails. We’re highly rated in the stock market. It hones your ability to do it less expensively, because we have to earn a profit.

MICHELLE ALEXANDER: There’s a whole range of corporations now deeply invested in the drug war and mass incarceration.

RICHARD LAWRENCE MILLER: And all these people are not trying to do anything wrong. They’re trying to make society better. But their actions, combined together, become part of the thrust that makes the bad parts of the drug war more feasible and more practical.

DR GABOR MATÉ: The thing with the war on drugs is, and the question we have to ask is, not why is it a failure, but why, given that it seems to be a failure, why is it persisting? And I’m beginning to think maybe it’s a success. What if it’s a success by keeping police forces busy? What if it’s a success by keeping private jails thriving? What if it’s a success keeping a legal establishment justified in its self-generated activity? Maybe it’s a success on different terms than the publicly stated ones.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re watching a clip, listening to a clip, of The House I Live In. The filmmaker is Eugene Jarecki. A remarkable—even remarkable to see Bernard Kerik in this clip, who is the former police commissioner, as you have identified him, prisoner because of his own corruption.

EUGENE JARECKI: The strange thing about the war on drugs, and I think the thing I hope to get across most to people, is that the war on drugs is something that was made by this country. We made it. It’s upon us. We have—you know, in our country, we’ve spent a trillion dollars on the war on drugs. It’s had 45 million arrests in 30 years. It has not reduced the supply, demand, use, sale or purity or availability of drugs. So it’s failed—there’s no one anymore who stands by it, maybe other than Bernard Kerik. But there’s almost no one I could get to tell me, “Yeah, this is a great idea.” They all say it’s a terrible idea, but how do you stop it at this point? How do you slow down something that is so immoral, so deeply misguided, but so powerful? And that’s the big $64,000 question we’re all trying to figure out. And by making the film, I’m hoping the public can get into that question in a more engaged way.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about some of the other figures in this documentary, The House I Live In.

EUGENE JARECKI: Of the numbers? Well, you know—

AMY GOODMAN: One of the people, I just want to say, who is quite compelling on how he describes this, because he has researched it for so long, is David Simon, who did The Wire.

EUGENE JARECKI: Sure, sure. Well, you know, after I spoke with Nannie initially about her own family experience with the drug war—her firsthand experience is of drugs. I mean, she’s a kind person, so, fundamentally, she is—she feels pain about loved ones suffering from the most immediate thing she can see, which is drugs. But I even know, from her own reporting to me about her own life over time, that it’s not just the drugs. It’s that drugs then get made worse by our criminal justice practices, which have been proven to be racist, misguided, driven by the kind of propaganda that surrounds drugs.

And so, members of her family, over time, who had issues with drugs didn’t meet the kind of—you know, she says, “You can put a man on the moon. Why can’t you deal with this?” Well, the question is, where is the political will to deal with it? If you have a public health issue, and you instead treat it as a big opportunity to build the prisons and to have industrial interests benefit from that and politicians who can get elected saying, “I’m tough on crime,” you end up creating a statistical mess on your hands, we’re sure. We have more black men incarcerated today, in one form or another, than were enslaved at the end of slavery 10 years before the Civil War ended. That’s a shocking statistic.

AMY GOODMAN: And the effects from housing.

EUGENE JARECKI: Think about that. Think about the effects on—

AMY GOODMAN: Voting.

EUGENE JARECKI: If you go to jail, you come home, you—for the rest of your life, as Michelle Alexander says in the film, you have to sign that dreaded—you have to check that box, that dreaded question on a job application: “Have you ever been convicted of a felony?” And that stays with you forever, and it affects everything. It affects whether you can live in public housing, whether you can get food stamps, whether you’re eligible for any of the things that then help you find your life back, if you ever had a life to begin with. And so, then we see that we have the highest recidivism rates of any Western nation, apart from the fact that we’re the large—world’s largest jailer and the rest. And so, my mission, which started with her feelings about the people she loved, who I loved, through her, became a study of why it hasn’t been more morally and decently and honorably approached as a public concern.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you see this, Ms. Jeter, as a racist war?

NANNIE JETER: Yes, I do, because when you—when he was speaking about voting, we have an ex-governor that spent time incarcerated, and he went right back into politics. So, and yet, still—and that’s what I look at. Those that in high places can pull time and come right back and vote and run and get almost back in the same position they were in for, that’s a double standards. That is. You can do it for one, and the same people are against the lone man whilst you are doing what you have changed against someone else. And it’s not fair. It’s about fairness.

AMY GOODMAN: Eugene Jarecki, you actually go with cops to do a drug raid.

EUGENE JARECKI: We do. And, you know, one of the wonderful things is—you could get really hopeless making a movie like this. We have, you know, 2.3 million people incarcerated in America. That’s 1 percent of our population. We are the world’s biggest jailer, beyond countries that are totalitarian in nature. You look at the country, and you see how unfairly the laws are written. You see that crack has historically been punished a hundred times as severely as powder, and that that seems no accident, whether it was an accident when it started or not. Over the years, jurists and judges and doctors and experts said this is wrong, it’s unfair, and it’s not based on science. Crack and powder are chemically the same, so why is one being punished that way. When you see all of that and you work with people in prisons and you talk to people who are at close range of this, you could really get very despairing, because the stories of people are—touch your heart in a very deep way.

But the reverse also happens, which is, I get to talk to Nannie, and she tells me things of so much honesty and so much depth about the issues she’s living through. And she’s not lost any fight. She’s not given up on grandchildren she even has incarcerated right now. To be perfectly fair, the grandchild she has incarcerated right now is the son of her son who died from drugs, to begin with. This cycle goes on and on, is infecting generations. So, could I lose hope? Yes. But until she says—I look over at her. She hasn’t lost hope. And then I talk to cops in the film, who openly tell me about what they’re doing, openly tell me that they don’t entirely agree with what they’re doing. They’re taking great jeopardy to appear in my movie and speak out critically about the way that police forces, for example, run on the money they collect from people. They bust a drug operation, as you’re going to see in this clip, and he’ll tell you in the clip, “We really run on the profits we get from these kind of operations.”

DAVID SIMON: We like to believe that the drug war has given law enforcement all these tools, all of this authority in which to pursue criminality and gangsterism. But actually what it did was it basically destroyed the police deterrent in a very subtle and unintended way.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s David Simon of The Wire.

SGT. BILL CUNEEN: Going up to 15th Street and Dixie. He’s going to have some crack for him and some oxycodone pills.

Joe and I are both sergeants in major narcotics, and we don’t do street-level drug deals.

Start thinking about why you’re in handcuffs, and maybe you can help yourself out, OK?

What happened is, the second guy, he’s now running on foot. Yeah, that’s where—we believe he might have gone in there.

I guess we’re going to have to write this up as a separate case. Totally unrelated to the original drug deal we did, but we stumble upon a house where a couple of big stacks of money, a good amount of marijuana. That’s sometimes how things happen. They’re not even planned.

DAVID SIMON: There are lot of detectives who I admire for their professionalism, for their craft.

SGT. BILL CUNEEN: Hey, what’s up? Can I help you?

PASSERBY: No. No, sir.

DAVID SIMON: But the drug war created an environment in which none of that was rewarded.

SGT. BILL CUNEEN: Get his ID. He was just cutting through the yard. All right?

DAVID SIMON: A drug arrest does not require anything other than getting out of your radio car and jacking people up against the side of a liquor store. Probable cause? Are you kidding?

The problem is, is that that cop that made that cheap drug arrest, he’s going to get paid. He’s going to get the hours of overtime for taking the drugs down to DCU. He’s going to get paid for processing the prisoner down at central booking. He’s going to get paid for sitting back at his desk and writing the paperwork for a couple hours. And he’s going to do that 40, 50, 60 times a month, so that his base pay might end up being only half of what he’s actually paid as a police officer.

POLICE OFFICER: The most important thing, right here.

DAVID SIMON: We’re paying a guy for stats.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s a clip from The House I Live In. Eugene Jarecki, take it from there, this raid, and going—you also speak with judges.

EUGENE JARECKI: Well, throughout the history of the war on drugs, it has gained a greater and greater number of critics on the inside. The people we spoke to who gave us the deepest criticisms of this system operate within it. Security Chief Carpenter, who’s a—he is the head of security at a major prison in Oklahoma. I thought he was—he looked like the toughest guy I’d ever met in my life. I thought I would—he’s a terrifying person to look at. I wouldn’t want to be under his lock and key, if you paid me. I get to sit down to talk to him, and I discover he has very deep and textured views about the wrongness of the way in which we incarcerate and we put so many resources into handcuffs, more cops, tougher laws. And where do those resources come from? They come out of the very programs in a prison that would help somebody not become a repeat offender, help them gain a skill, build some life elements that they will need when they get out, so that they don’t go the way of Nannie’s son, who was in and out of prison and not getting that kind of care.

AMY GOODMAN: In The House I Live In, in Oklahoma, you talk about the draconian laws there and a guy caught on possession of meth—

EUGENE JARECKI: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: —three times. His sentence?

EUGENE JARECKI: Well, there’s a guy in the film named Kevin Ott. And Kevin Ott is in for life without parole for a nonviolent drug crime. And he has no violent drug crimes in his history. He has three-in-a-row possession. So he got a three strikes—

AMY GOODMAN: That’s three strikes, you’re out.

EUGENE JARECKI: —and you’re in for life without parole.

AMY GOODMAN: Life without parole for possession.

EUGENE JARECKI: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: You have people like Bill Clinton, the president, saying, “Three strikes, and you’re out, and we’re proud of that.”

EUGENE JARECKI: Yeah, and they’re doing it. And it’s—I think when Americans see that, and without working only along racist lines, I would say, when Americans see a relatively middle-class white American like Kevin Ott in there, they go, “Wow! This isn’t just happening to other people? It’s happening to guy who kind of looks like my uncle?” Now, I don’t think that’s how people should think. I think they should care already when it’s happening to another person. But for some reason, in this society, a lot of times you have to wake people up by their neighbor or their brother or their uncle.

AMY GOODMAN: Very quickly, the solution?

EUGENE JARECKI: What’s my view of the solution? The first thing is that you need to have a very changed dialogue in this country that understands drugs as a public health concern and not a criminal justice concern. And that means the system has to say, “We were wrong.”

AMY GOODMAN: And do you think we’re going to have that in this election year, when sound bites are nine seconds, and the drug war, and the victims of it, the perpetrators, etc.—

EUGENE JARECKI: Yeah. I mean, I’m not a dreamer on that score, but I do believe there is so much wrong with this, it is showing its weaknesses so terribly, and other countries are shaming us, like Portugal, where they’ve made drugs legal and it’s working, and things like this.

I believe that making drug activity that is nonviolent in nature illegal was a grave mistake in this country. If you want to say that violent activity is the province of the law, and we should protect ourselves, one from the other, from rape, robbery, murder, the classic things that we use police for and that we use laws for, I perfectly agree with that. I think Nannie would. Anyone would. And if you take a drug and it makes it worse, it’s no different than if you got in a car and you hurt someone with your car, it might be manslaughter. If you were drinking, they’re going to call it murder. It’s going to enhance. It should. Drugs should be seen in that way. But alcohol, which is more dangerous than all of them, has laws applied to it that basically say it’s legal to do unless it’s an enhancer on you driving. Well, let’s make drugs that.

So, in other words, I would say, let’s stop talking about legalization versus the most draconian system in the history of the world. Let’s talk about no more having it be illegal to engage in nonviolent drug activity. I think millions of Americans, who use drugs anyway, and we all know that everybody uses drugs in this country—we are the biggest drug-using country in the world—everyone will cheer for that, because they are still protected, one from the other, but we’re not doing something that is so deeply on the wrong side of history. It’s obvious.

AMY GOODMAN: Ms. Jeter, since Eugene calls you his second mother, you helped raise Eugene, how do you feel he turned out?

NANNIE JETER: Well, I—

EUGENE JARECKI: You can be honest.

NANNIE JETER: Well, my children call him my son. When the phone ring, they say that’s her other son. And he is like my son. This family, I love, is three them. And the oldest one called me, and I almost wept. I never met a family like this. And I knew Eugene—

EUGENE JARECKI: I have two brothers.

NANNIE JETER: I knew Eugene before he was born. Matter of fact, I was his, supposedly, nurse, because his mom was tired of nurses. Something happened. So, I was in their home when Eugene came home, when his parents brought him home from the hospital. And I have loved him ever since. And I talked about him, and I didn’t know my sons were jealous of him, because when I would come home, all I would talk about was Eugene, Eugene, and Tommy and Andrew.

EUGENE JARECKI: And that’s complicated. That’s a complicated part of the history, you know, and it’s something we deal with in the film, because for somebody like me and Nannie, we’re just in a system where she’s looking for work, she’s got a job with a family. My family left Connecticut. She traveled with us. That left her son, who got into drugs and other things, unguarded, to some extent, by her. She feels a weight in her about that. I feel that neither of us is to blame for that. It’s a system. It’s an economy in this country that has lots of people driving long distances to work, today on even more expensive gas than ever before. Like, it’s a tough time, and it has been for a long time. And she and I, within that, just have a real love for one another.

But I think we’re both kind of aware of the complicated political dynamics of who we are. I learned a lot of that from her, because she would say to me things like that, and I don’t know, am I supposed to feel guilty about that? Or how am I supposed to feel? And I didn’t do anything wrong. I just love her, and she really loves me. But, for example, when I meet her kids, I’m aware that time spent toward me is time not spent toward them when I was a kid. That matters. You can’t take that for granted. It doesn’t have—it’s not about blame, but it’s just a fact that needs to be understood, if we’re going to make the world better and have it not be that way.

AMY GOODMAN: Director Eugene Jarecki, along with Nannie Jeter, the woman who helped raise him. She’s one of the film’s main characters. Jarecki’s film, The House I Live In, won the Grand Jury Prize for U.S. Documentary this past weekend at the Sundance Film Festival. We spoke in Park City, Utah, at the Sundance headquarters.

![]() The original content of this program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. Please attribute legal copies of this work to

The original content of this program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. Please attribute legal copies of this work to democracynow.org

. Some of the work(s) that this program incorporates, however, may be separately licensed. For further information or additional permissions, contact us.